Hackweek 2026: What happens when a physics lab stops research for ~two weeks

Research labs are exciting environments where we learn, discover and invent new things. But they can be weird as well. You can have someone who fabricates superconducting qubits or photonic circuits and builds systems that operate at the limits allowed by the laws of physics, but who has never written a line of code outside of MATLAB (or even worse, Mathematica).

This is fine, mostly. Depth is the whole point of a PhD. There's just not enough time to learn everything. We pick our battles. But it also means there's an enormous amount of low-hanging fruit that just doesn't get picked. There could exist all sorts of tools that would make everyone's life easier, and we often say "oh, I wish we could just build something that ...", but that nobody builds because it's "not my area", and "takes too much time away from research", etc. All completely valid excuses. More importantly, we just don't experience all the personal satisfaction that comes with building and shipping small things ... but c'est la vie...

Or is it? In the last year or two, AI coding tools have gotten good enough that "I don't know how to do that" is no longer a reason not to try.

So we decided in our group to do something about it. In January 2026, we ran our first lab Hackweek.

The pitch

Here's roughly what I proposed to the group in December 2025:

Hackweek 2026

What is it? A short, optional "build sprint" where small teams pick a project and try to ship a working demo in about one week.

Why? Get outside our comfort zones and build stuff we don't know how to build. Use modern AI tools — LLMs, coding assistants, agents — to learn fast, prototype quickly, and debug efficiently. Share techniques that help us move faster in research.

What is success? Learning a bunch of new things you normally wouldn't in the course of doing research. A demo-able prototype. Bonus points for something that can be reused by the lab.

I want to emphasize that success IMO is defined as learning, not shipping. A working demo was just the cherry on top. The main point was to step out of our comfort zones and learn these tools ... how else can we learn them? It also meant people chose ambitious projects ... things they genuinely didn't know how to do ...

A bunch of ideas emerged from the group... the list was all over the place:

- Ultrasound bat detector (this one was by me and I'm still working on it on the side...)

- Lab agent that aligns a fiber to a chip

- Injection-locking a mechanical watch to a MEMS oscillator

- Fab "copilot" powered by RAG

- VR training programs for using the dilution fridge (!!!)

- Automated RF probing across a die

- Cryo-compatible HEMT LNA from Minicircuits components (100 bux vs 5k commercial)

- SPICE circuit simulator as a web app (what I actually ended up doing)

- LEDs generating analog Turing patterns

- ... And about fifteen more

Hardware to software. Instruments to web apps.... The common thread was: I don't know how to do this, but let's see if we can figure it out in a week.

The format

We immediately decided it should actually be two weeks, to enable a bunch of tutorials in the first week.

- Two weeks (Jan 9–23), optional participation

- Day 1: Kickoff + tutorials. Kaveh ran a session on machining, CNC, and 3D printing. Illustrious LINQS alumnus Wentao Jiang (outsidefivesigma) gave an overview and kicked off the whole thing. People pitched projects and formed small teams (~2 people).

- Week 1: Tutorials continued: Nelson on app development with Expo/React/Cursor, Tolga on VSCode + GitHub Copilot for LaTeX, Jason on other tools. Then: build, build, build.

- Mid-point Friday: Hangout / debugging / integration session

- Final Friday (Jan 23): Demos + short presentations

Prizes: a CNC plaque on 3d-printed trophy, eternal glory, and a shout-out from Wentao.

We had a communal parts-ordering spreadsheet for hardware projects. The whole thing was intentionally low-overhead.

The projects

Here's some of what came out of it. I'd like to try describe each one because I think they're all genuinely interesting, but being practical, I'll just go deeper on a few, and let the people who did the work explain things in more detail...

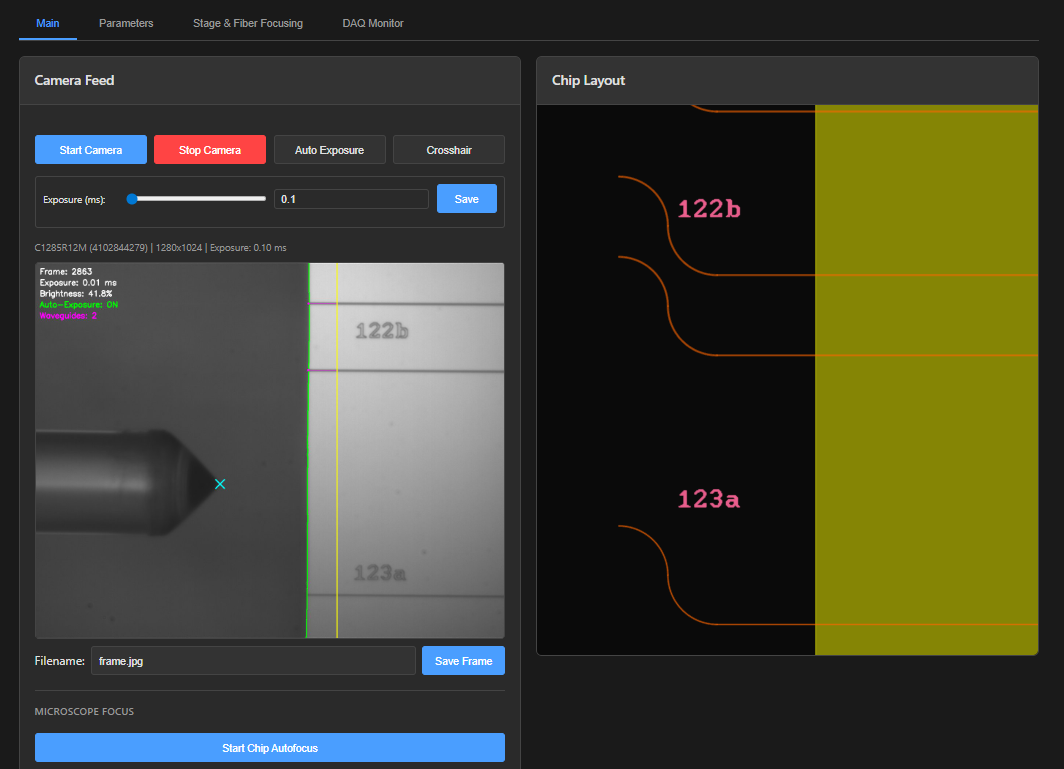

Optobot: Autonomous fiber alignment with computer vision

Ethan Rosenfeld, Pau Molet Bachs, Michelle Qin, David Concepcion

If you work in nanophotonics, you know the pain of coupling light from a fiber into an on-chip waveguide. Step 1 is coarse alignment — a human squinting at a microscope camera, nudging translation stages. Step 2 is gradient ascent on the detected power. Step 1 is tedious. Step 2 gets stuck on local maxima (slab modes, etc.).

Optobot replaces Step 1 with computer vision: it recognizes waveguides and fibers in the microscope image and drives the stages automatically. Then it uses a smarter optimization algorithm for Step 2 that avoids the local maxima problem. The result is autonomous measurement of nanophotonic devices. This is the kind of tool that, if it works reliably, changes the throughput of an entire lab. Also the smooth operation of it, just clicking on a spot and seeing the fiber under the microscope magically appear there had a huge "wow" factor during the presentation.

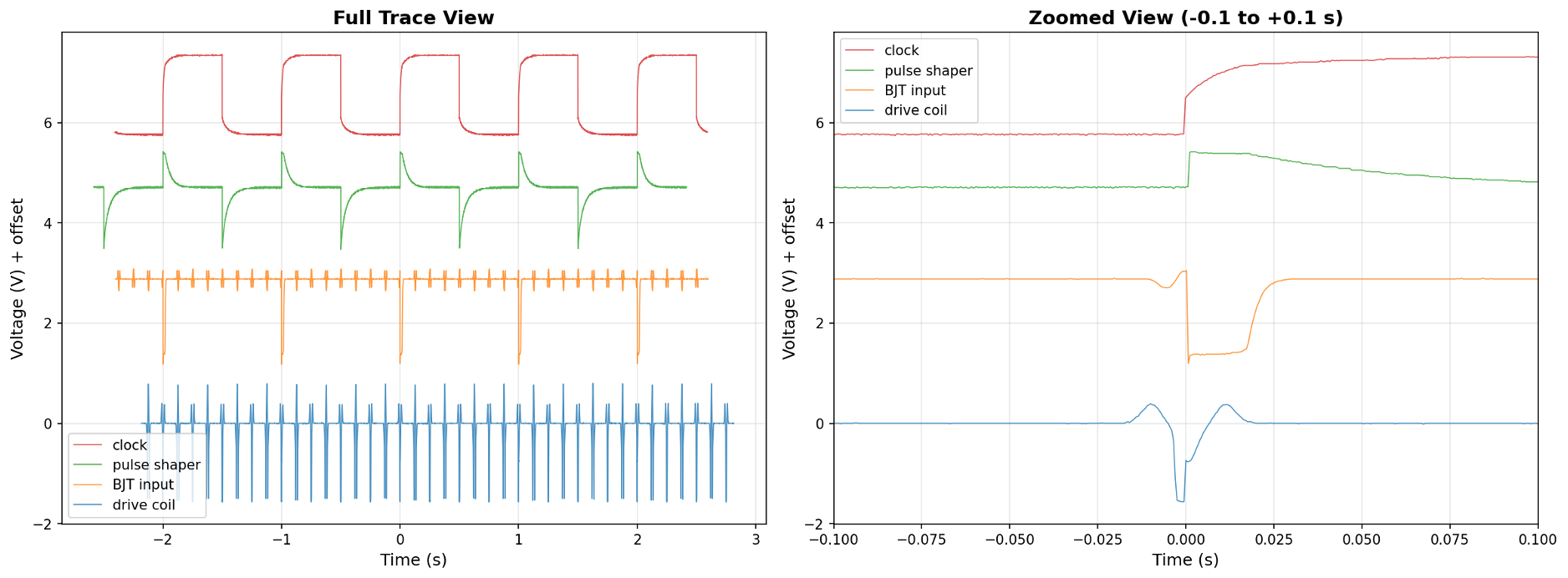

MEMS-locked mechanical watch

Kaveh Pezeshki

This one is hard to summarize because it's so beautifully Kaveh. Mr. Pezeshki took a 1970s Seiko Elnix 0703A, a transistorized mechanical watch, and injection-locked it to a SiTime MEMS oscillator. The MEMS oscillator provides a stable frequency reference; a passive pulse shaper and transistor coupling inject this into the watch's electromagnetic loop.

Kaveh, as usual, constrained himself to completely in-house fabrication. No external PCB vendors. The PCB was milled on a desktop CNC. Wirebonds were done by hand for fine-pitch SMD connections. The caseback was machined from 6061 aluminum. The display window was laser-etched mineral glass. Everything built from scratch in the lab.

The result: stable over 2+ weeks at roughly +1 ppm — about 2 orders of magnitude more precise than the stock mechanical movement. The watch is slightly thicker than the original, but no one's perfect.

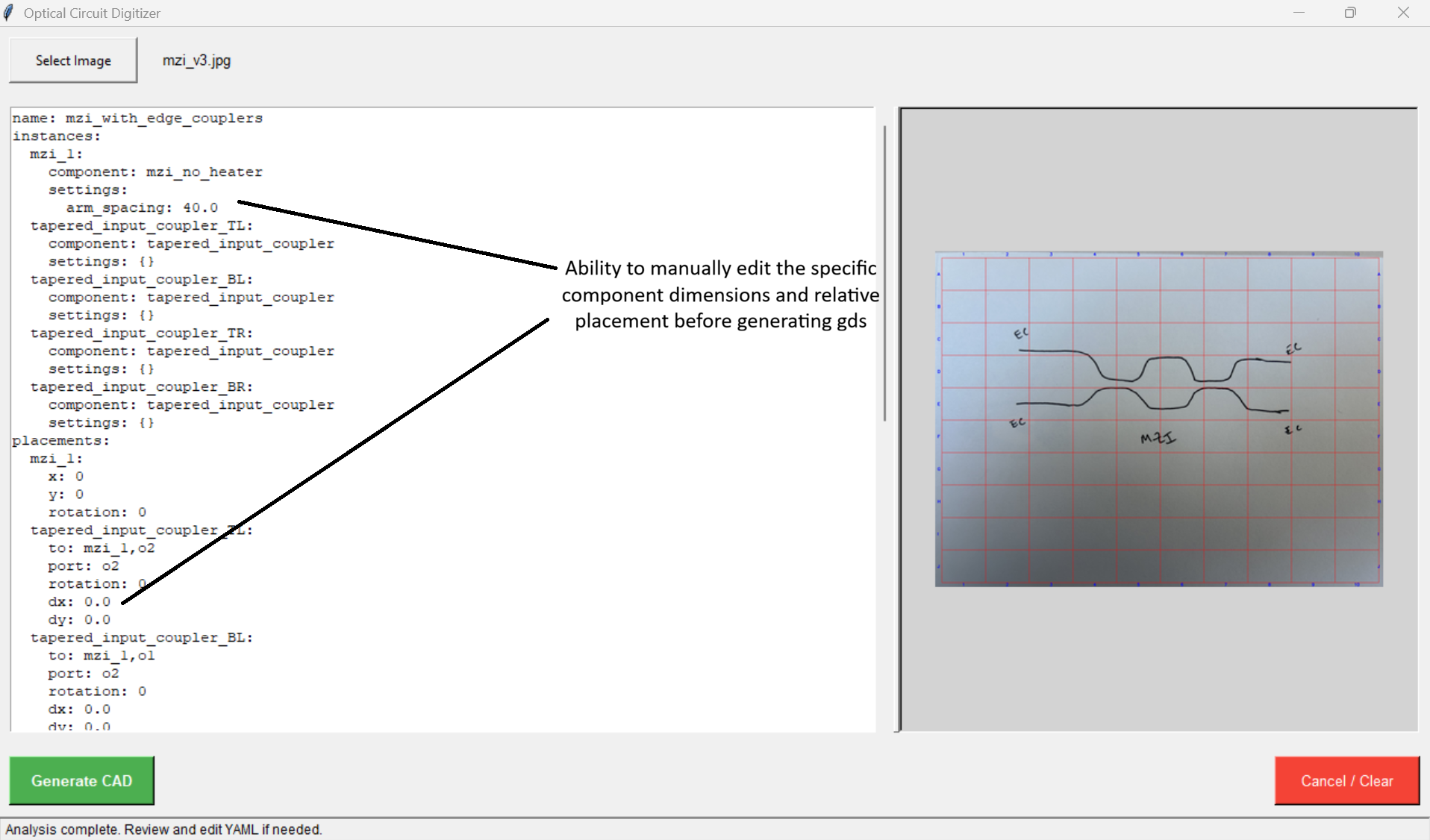

Draw to CAD: Hand-drawn circuit sketch → GDSII

Linus Woodard, Sam Robison

If you design photonic circuits, the workflow is usually: sketch something on paper or a whiteboard, then spend a while re-creating it in a scripting environment (GDSFactory, gdspy, etc.) to get fabrication-ready files. What if you could skip the middle part?

This team built a pipeline: upload a photo of a hand-drawn circuit. The app overlays a grid. Google's Gemini vision model analyzes the image and generates a structured YAML description of the circuit — components, connections, positions. The user reviews and edits the YAML, hits "Generate CAD," and GDSFactory produces a GDSII file ready for lithography.

Concept sketch to fabrication mask in minutes. Is it perfect? No — vision models still struggle with messy handwriting and ambiguous routing. But as a rapid iteration tool for getting from idea to first-pass layout, it's remarkable.

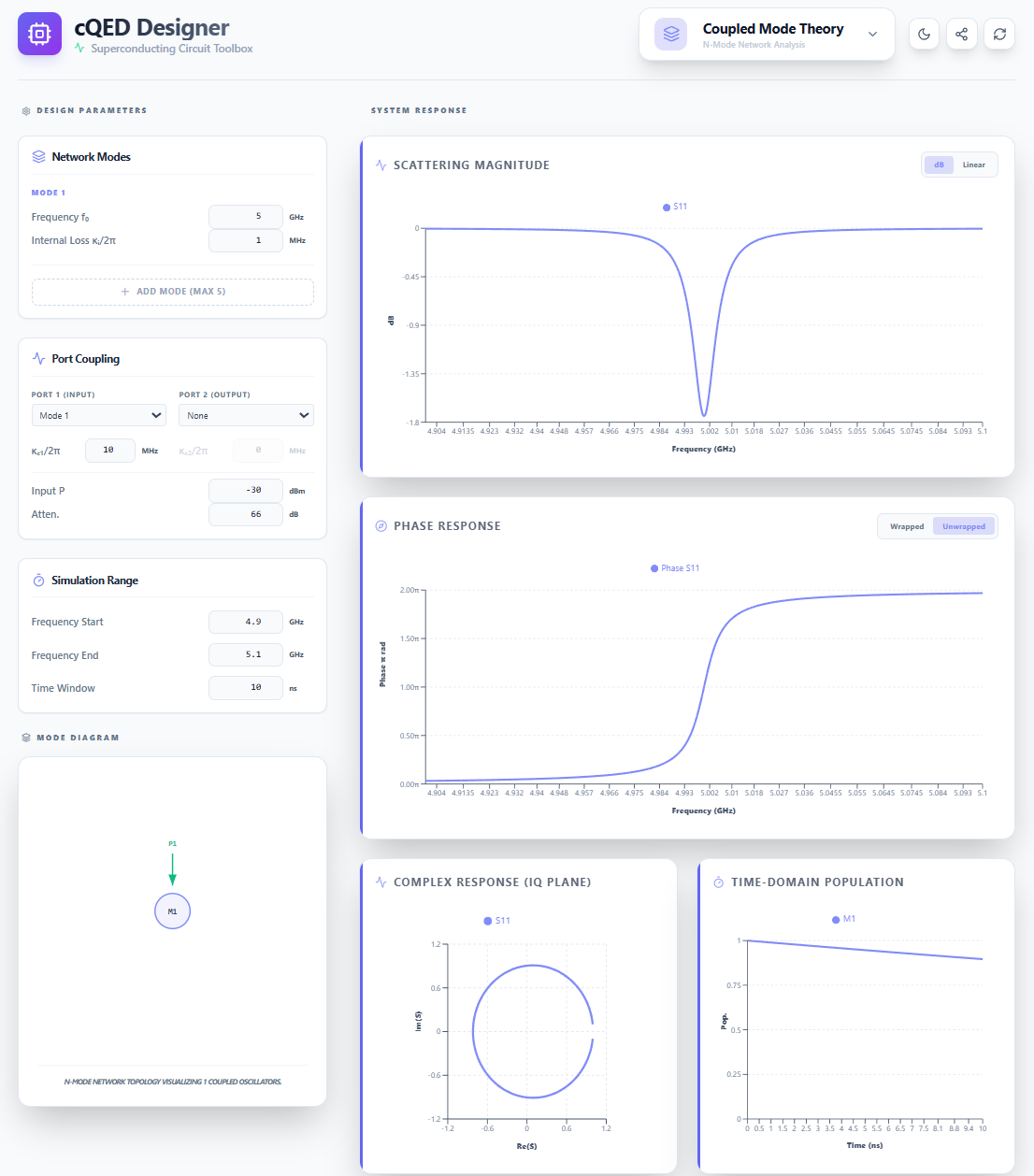

cQED Toolbox (c-qed.com)

Sultan Malik

Sultan built a browser-based calculator for common circuit QED problems: single qubit-resonator systems, two qubits coupled via a tunable coupler, general coupled-mode problems, plus assorted microwave/photonics/optics calculators. It runs entirely in the browser (no backend).

This is the kind of tool that replaces scattered back-of-envelope calculations and ad-hoc Mathematica notebooks. You open a browser tab, punch in your parameters, and get the answer. New students can use it on day one to build intuition. It's live at c-qed.com.

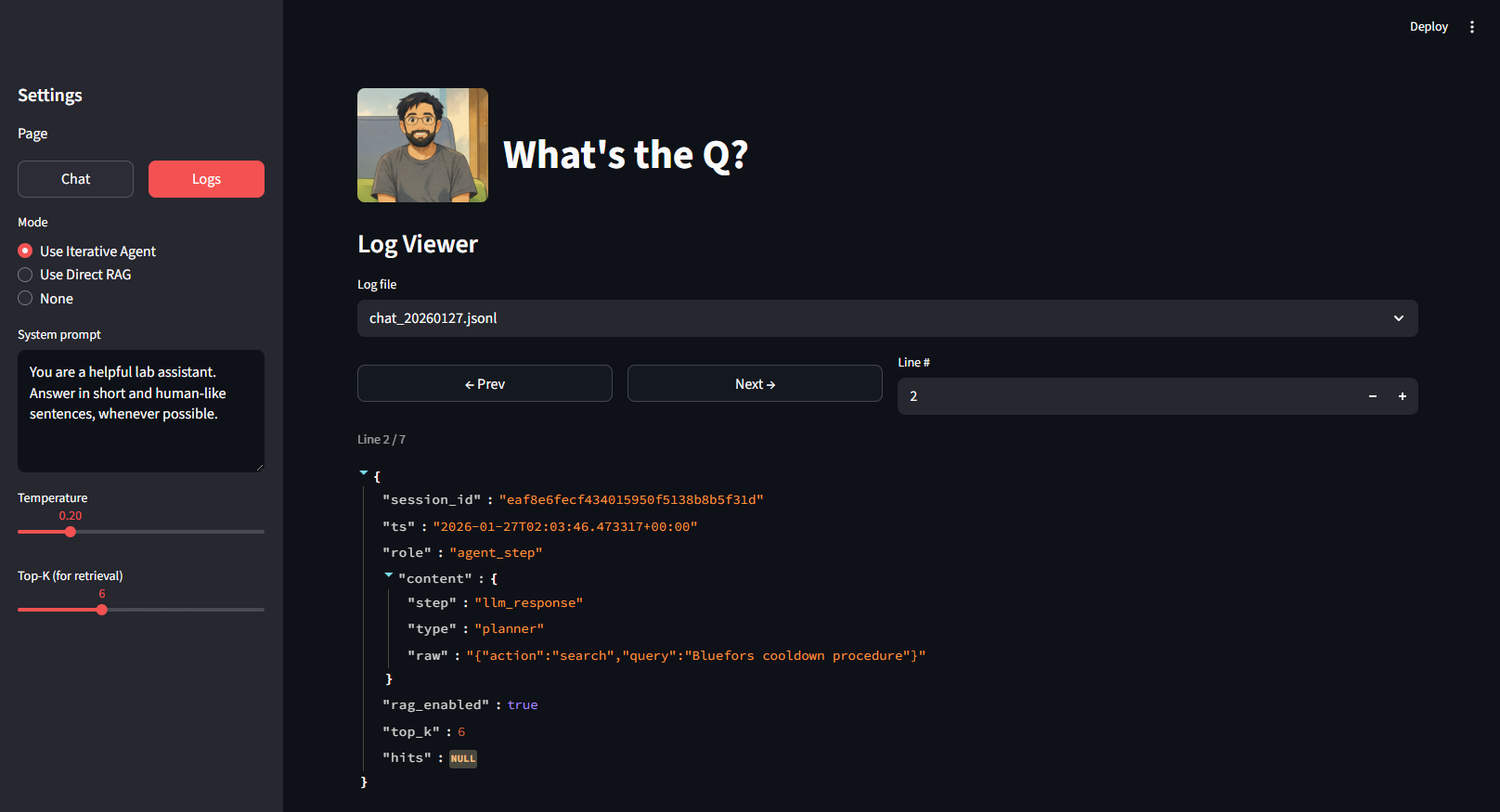

Lab RAG Agent

Zelong Yin

Zelong built a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) system for searching our lab's documentation. You ask a question — "What's the SOP for the Plassys e-beam evaporator?" or "What etch recipe did we use for the last LN run?" — and it retrieves relevant document chunks, then uses an LLM to synthesize an answer with citations.

The interesting technical detail: hybrid retrieval using both semantic vector search and BM25 keyword matching, merged with reciprocal rank fusion. It turns out this matters a lot for lab documentation. Semantic search alone misses equipment names and process parameters — if someone writes "PECVD" or "Plassys" or "AZ5214," you need exact keyword matching to find it. The hybrid approach handles both.

The system has two modes: basic retrieval (single-round search) and an agent mode that iteratively reasons and performs multiple search rounds for complex queries. It runs on our lab ethernet, with a Streamlit web UI and ChromaDB for storage.

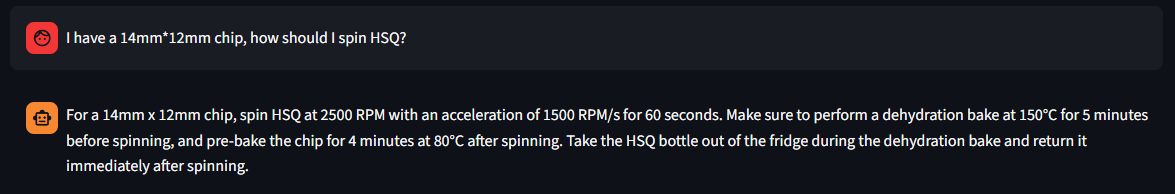

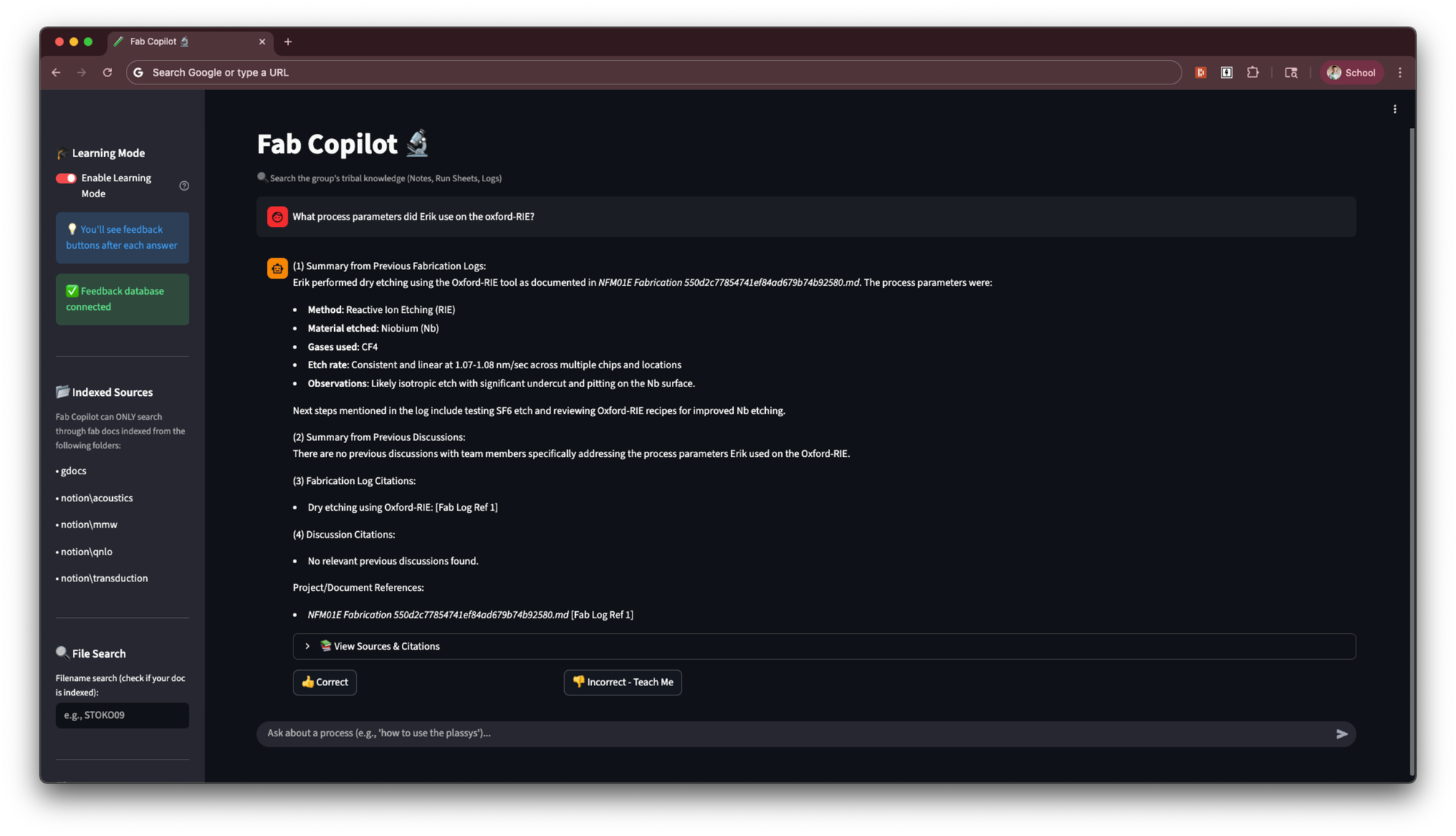

Fab Copilot

Alex Hwang and Takuma Makihara

The Fab Copilot team independently converged on the same idea as Zelong — a RAG system for lab documentation — but focused specifically on nanofabrication process notes. Their twist: before embedding, an LLM pre-processes the raw fab notes (which tend to be messy, abbreviated, inconsistent) into clean, human-readable steps. This turns out to be important because the quality of your embeddings depends on the quality of your input text, and raw fab notes are... not great.

They also found the same thing Zelong did: keyword retrieval is critical for lab-specific jargon. Two teams, working independently, arriving at the same architectural conclusions. Everyone wants searchable lab knowledge; nobody has figured out the right product yet. That itself is interesting.

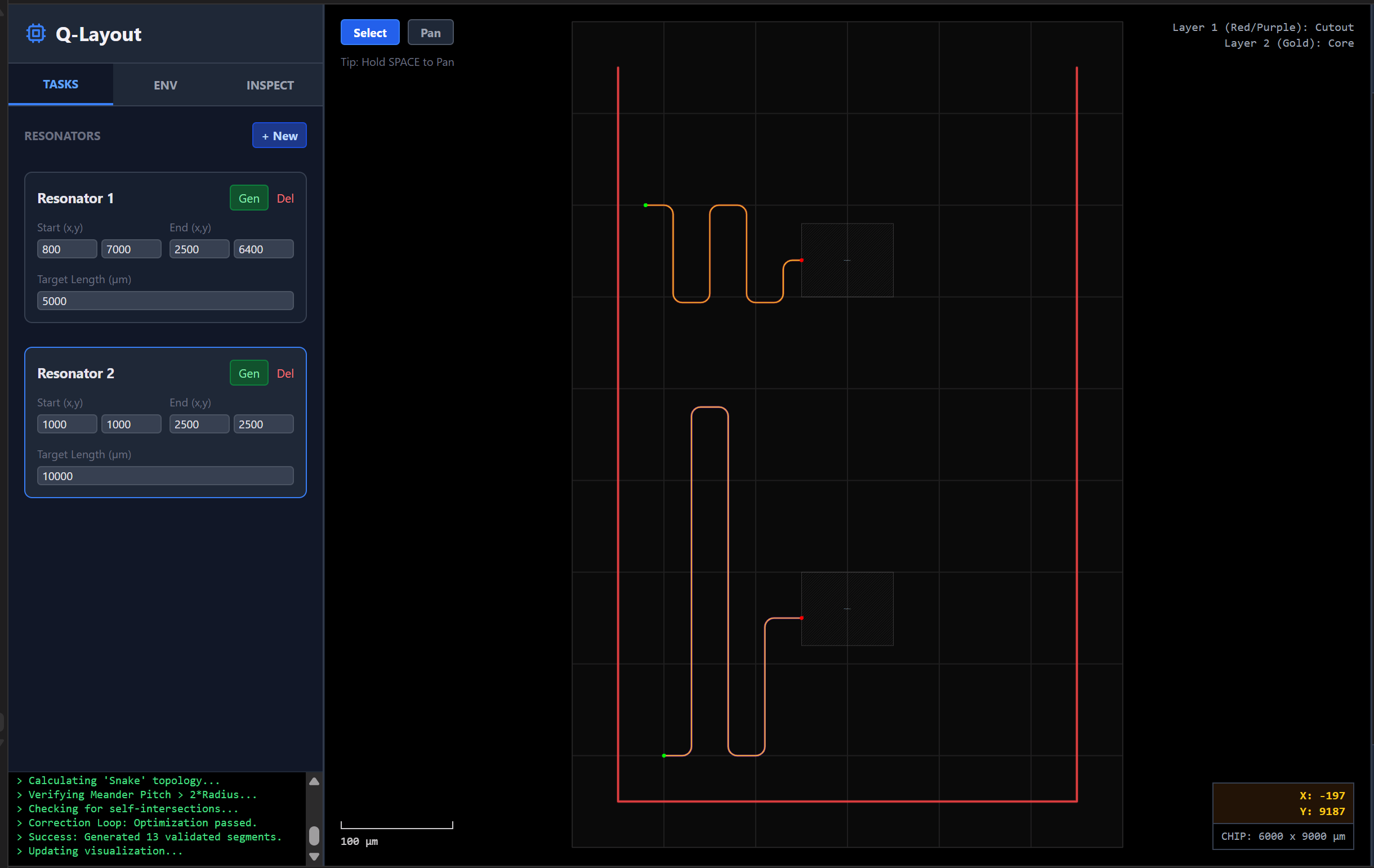

Smart Chip Router + Notion Migration

Chou-Wei Kiang

Chou-Wei built three tools, I'll tell you about two of them:

Notion × LLM Summarizer: Extracts Notion databases and pages, sends them to your LLM of choice (supports Google, Claude, OpenAI, and even local models via Stanford's AI Playground), and patches summaries back. Bypasses Notion AI's $20/month/user paywall. (we love notion but their AI costs are egregious for an academic lab)

Smart Microwave Chip Router: This one's more niche but very cool for our field. Manually routing transmission lines on microwave chips — CPW resonators, qubit drive lines — takes days per design. CWK built an EDA-like tool that routes based on constraints (frequency, device location, chip size) and outputs Python scripts for GDSFactory. It renders in real-time using an SVG engine with collision detection and coordinate transformations.

Convex: AI IDE for Research Teams

Nelson Ooi

Nelson is building an AI-powered IDE specifically for research and hardware teams — instrument setup in a few clicks, connection debugging, integrated planning and control testbenches. It's in early development and he's keeping the details under wraps until closer to launch. Worth watching.

Now, you may have noticed Kaveh's name keeps showing up. He did three projects during hackweek, here are the other two:

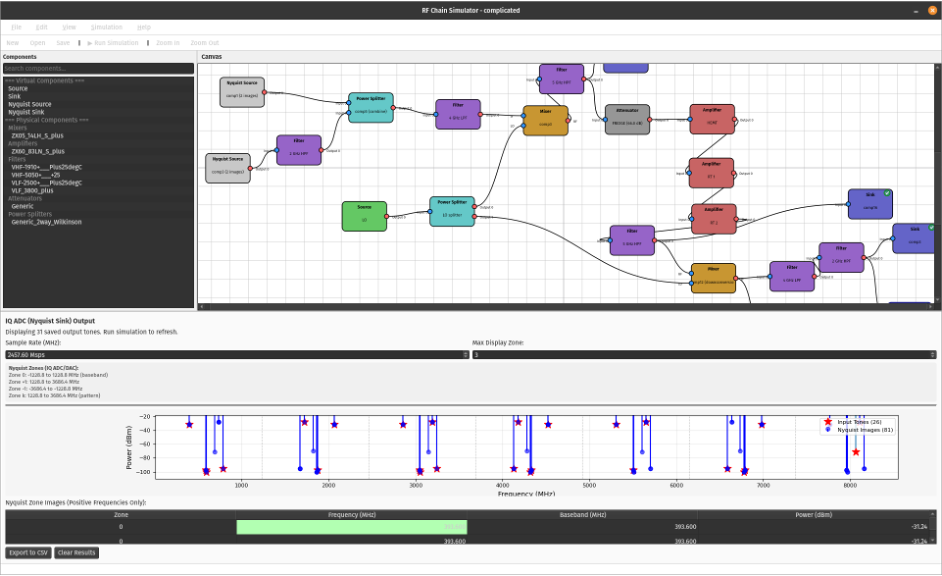

RF Chain Simulation GUI

Kaveh Pezeshki, again

Cryogenic microwave experiments involve complex signal chains — sources, power splitters, amplifiers, mixers, filters — running through multiple temperature stages. It's easy to lose track of spurious signals, images, or to accidentally drive an amplifier into compression. Kaveh built a GUI for simulating these chains: you define the components (with support for importing S2P files from manufacturers or VNAs), and it calculates signal propagation through the chain.

It's deliberately not a full RF simulator — it assumes perfect impedance matching and models only the first few nonlinearities. The point is speed and convenience for day-to-day experimental design. He built it using Claude Code, and it's already in active use in the lab.

HP 8593A Spectrum Analyzer Repair

Also Kaveh Pezeshki, again

Two broken HP 8593A spectrum analyzers. Problem 1: both showed video output but no display — traced to high-ESR capacitors on the CRT driver board. Problem 2: amplitude offset on one unit — tracked to a stuck step in the frontend mechanical step attenuator. Temporarily unstuck, needs a full rebuild for a permanent fix. This kind of equipment repair is a dying art, and it's exactly the sort of thing that makes hackweek valuable: skills you'd never develop during normal research, but which save the lab thousands of dollars.

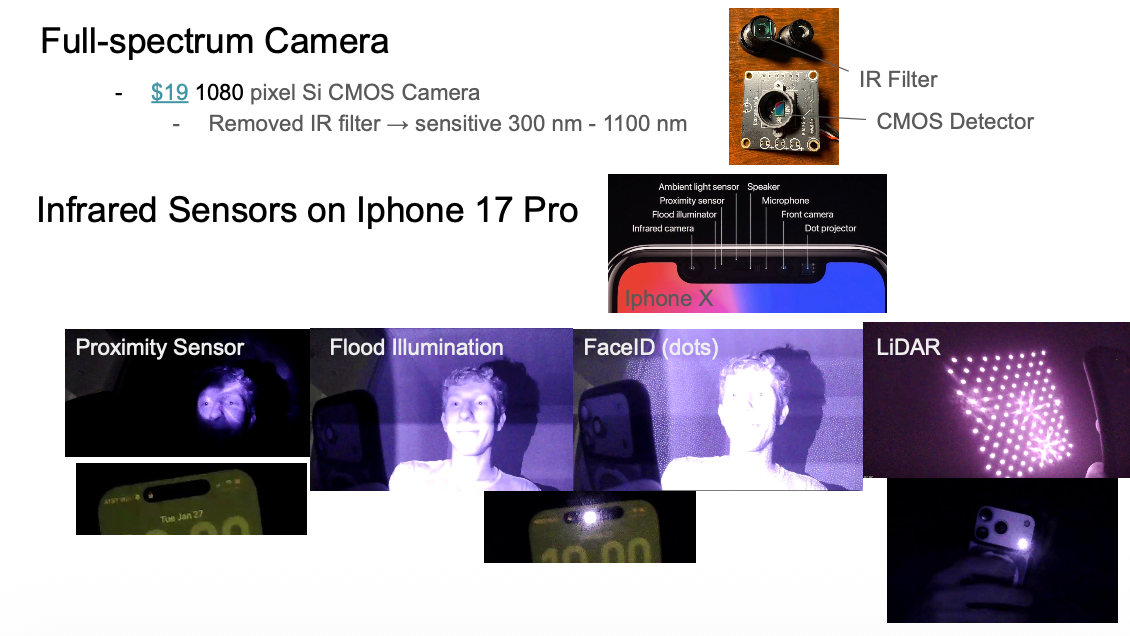

IR Camera Sensors in Smartphones

Devin Dean

Devin explored the infrared sensors built into modern smartphones — Face ID's IR dot projector, LiDAR depth sensing, proximity sensors, flood illuminators, and thermal imaging. He documented how each sensor works through hands-on experimentation with video demonstrations and frame-by-frame analysis! 😄

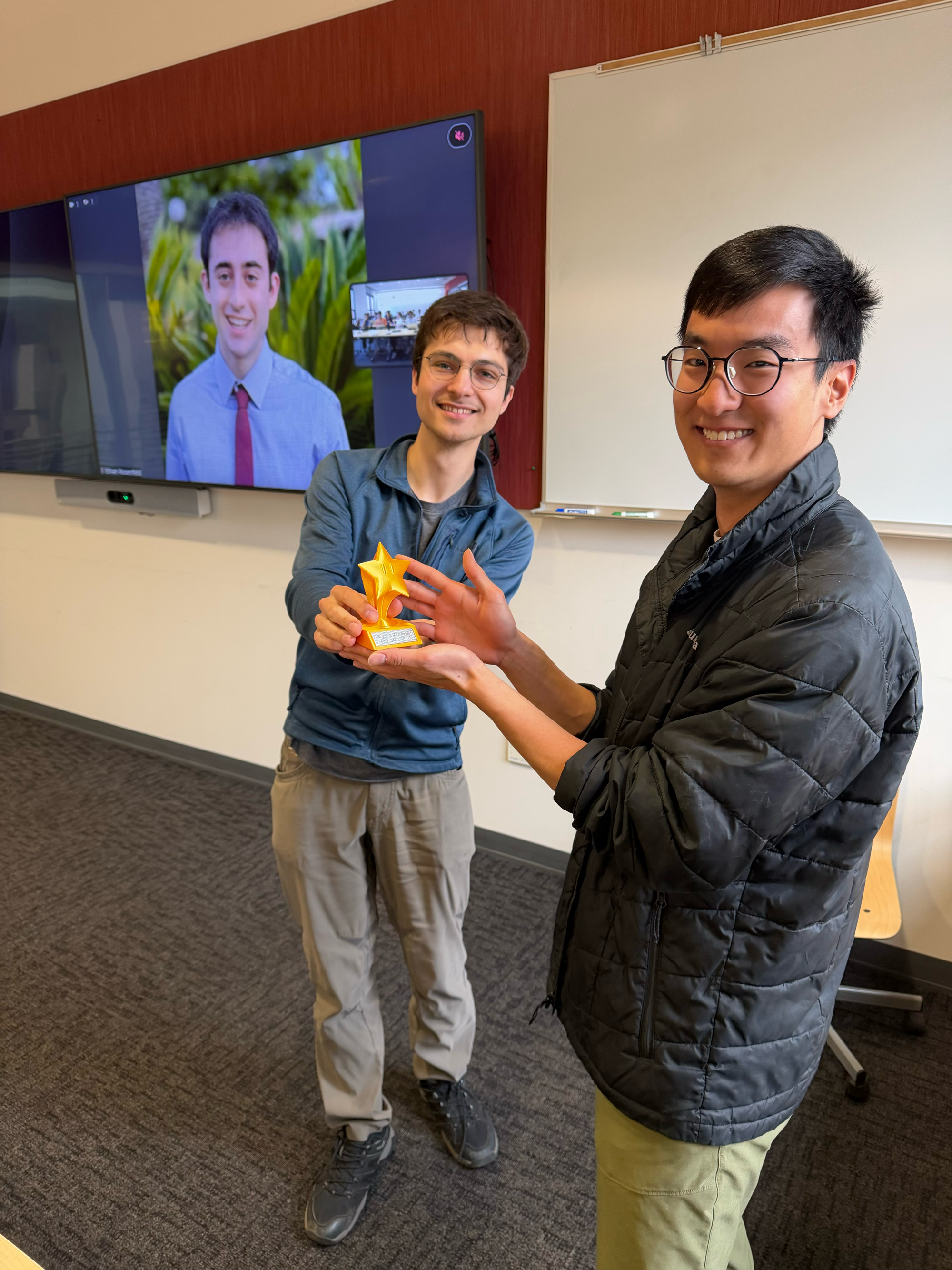

Awards

We held an awards ceremony at the end (by popular vote): Nelson took first place for Convex, and Kaveh and Sultan tied for second. Prizes were distributed. Glory was achieved.

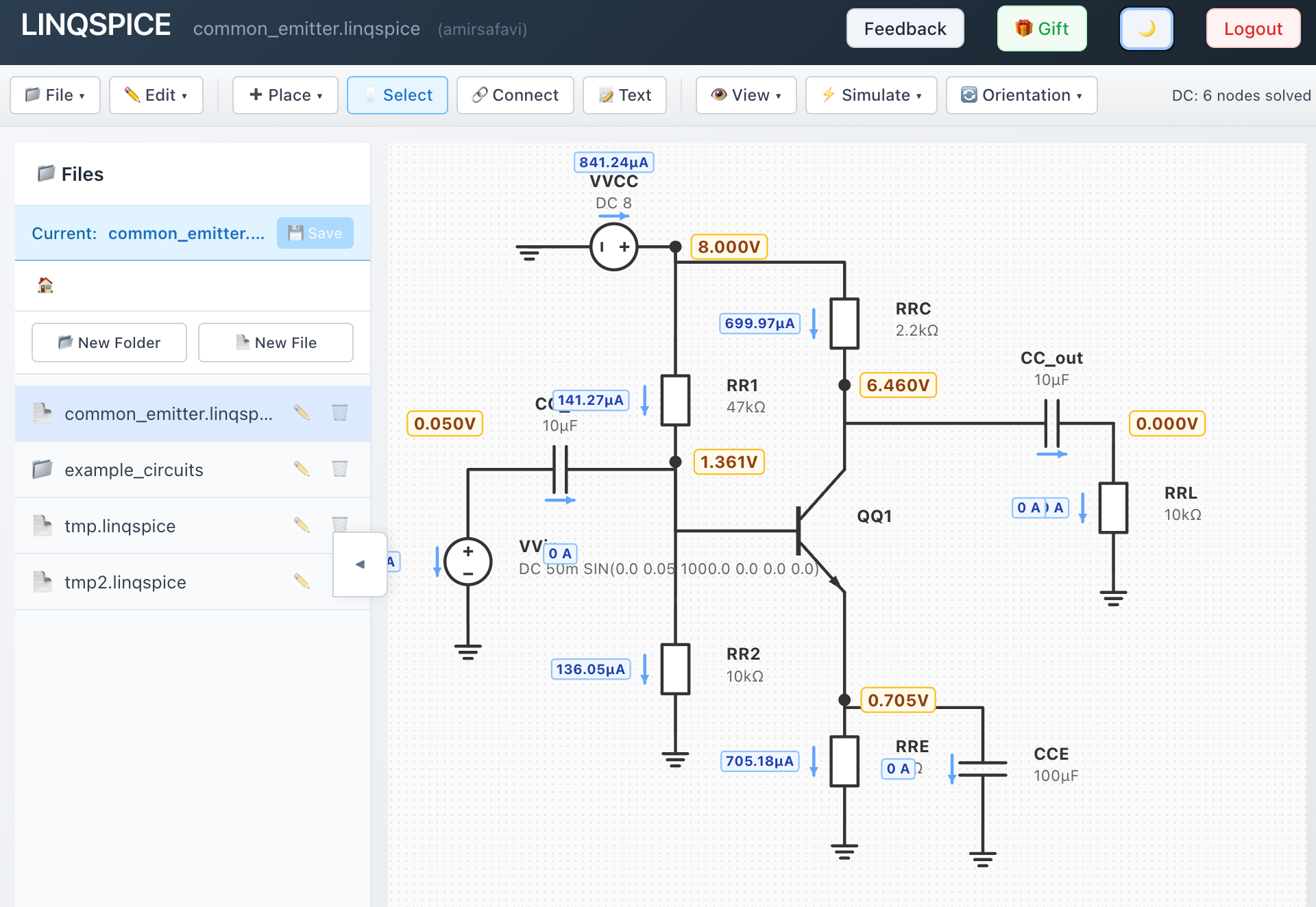

My project: LINQSPICE

One of the ideas on our brainstorm list was: "Cellphone app for doing _ (SPICE simulation, optics simulation, etc.)" That was my entry.

I don't normally write frontend code. Why lie, I don't write frontend code at all. But the pitch of hackweek is that you build something you don't know how to build, and I figured I should do it too, not just organize it.

LINQSPICE is a browser-based circuit simulator. You draw a circuit, hit simulate, and get results. It uses ngspice on the backend, a solid, open-source SPICE engine, with a React frontend and a FastAPI/Uvicorn server connecting them. The whole thing runs on an Oracle Cloud free-tier instance (I learned this trick from Dave Schuster).

I built most of the frontend with AI coding assistants. A combination of Gemini and Claude mostly. I'd describe what I wanted, the assistant would generate the React components, I'd iterate on the details. This is where the "leverage AI tools to learn fast" part of the hackweek philosophy became very concrete for me. I was writing TypeScript for the first time, and yet I had a working app in days.

I want students in my courses to be able to open a browser tab and simulate a circuit without fighting LTSpice. No install, no account (you just need a google account to log in, so your files are kept under under your file), no license. Just open the page and start.

Try it: www.linqspice.com

I think it matters that I did the hackweek too. If you tell your lab "get outside your comfort zone and learn something new," you should probably do the same thing. Also it was fun and addictive.

What didn't work

One week is actually not enough for hardware projects. So we changed it pretty quickly to two weeks. Designing a PCB, getting it fabricated at JLCPCB, and soldering it up is about 10 days by itself, and that's assuming nothing goes wrong. Even the two weeks we actually ran wasn't enough. If we do this again, hardware projects probably need a longer runway, or a different cadence. Kaveh tried to have group orders before start of hackweek and that was helpful.

I also didn't get to participate as much as I wanted. Between a program review, four hours a week of teaching, and various deadlines, my own hackweek contributions were squeezed into gaps. LINQSPICE took me well beyond the hackweek window to finish (poking it at low intensity via Claude code...). That's fine, but it's worth acknowledging: a PI's schedule and a grad student's schedule are different beasts, and "optional two-week build sprint" is different when your calendar is already full.

Other things we learned

AI tools have changed what "I don't know how to do this" means. This is the main takeaway. A year ago, many of these projects would have been impossible in one to two weeks. Not because the underlying ideas are hard, but because the skill gap between "I know what I want to build" and "I can actually build it" used to be enormous. LLMs, coding assistants, and agents have compressed that gap dramatically. Physics grad students who had never built a web app shipped production-quality tools in a week. Simple enough that even a PI can do it.

Multiple teams converged on RAG. Zelong and the Fab Copilot team, working independently, both built retrieval-augmented generation systems for lab documentation. Both discovered the same thing: hybrid retrieval (semantic + keyword) is essential for technical jargon. When different teams independently arrive at the same solution, that's a signal. Our lab (and probably every research lab) has a massive searchable-knowledge problem. I'm still not sure what the right product looks like here — but clearly the demand is real.

Hardware projects thrived too. It wasn't just software. KP's injection-locked watch, the ultrasound sniffer PCB design (in the works!!), the spectrum analyzer repair... AI tools helped with component selection, schematic review, PCB layout decisions, and documentation. The barrier to sophisticated hardware prototyping is lower than it's ever been.

The real output isn't the demos. It's a lab full of people who now know how to build things they couldn't before. People who can spin up a web app, train a RAG system, design a PCB, repair vintage test equipment. These skills compound. The next time someone in the lab says "I wish we had a tool that..." someone else will say "I can build that in a weekend." That's the actual return on investment.

It's really fun to make stuff. I wrote this twice in the original proposal, and I'll write it again. Research can be a long grind, measurements that take months, papers that take years, samples die, cleanroom tools go down, etc. etc. Hackweek is a reminder that building things is intrinsically fun, and that the fast feedback loop of "idea → prototype → demo" is energizing in a way that long research arcs sometimes aren't in the short term. We need a bit of both in our lives. AI can accelerate the deep stuff which needs to be always going on, but now there's a whole lot of fun, maybe more shallow things, that any of us can do.

Personally, this will help me stay in touch with the part of myself that wanted to get into this business in the first place.

We're planning to do this again. If you run a research lab and haven't tried something like this, I'd strongly encourage it. Keep it low-overhead. Make it optional. Define success as learning. And take part yourself.

If you want to try any of the tools: LINQSPICE and c-qed.com are live and free to use. I'll put LINQSPICE on Github at some point soon. Watch out for Nelson's app... coming soon :) – in the spirit of hackweek Claude helped me with writing this blog post

![Fidelity, Fisher Information, QCRB and All that [pt. 1]](/content/images/size/w600/2025/05/IMG_3285.jpeg)